On Raila Odinga: This will be... complex.

There's a reason why the man has many names.

First, the drop. The single, solitary tweet.

Then the trickle. A quote-tweet. A reply. A WhatsApp message, a screenshot of a tweet, a forwarded message from a cousin who knows a guy who works in the… you know. The usual Kenyan way of knowing things before they are things.

Then the pour. The posts everywhere.

If conversational heatmaps could be visualised, this one would be white-hot.

—

“Umesikia?”

The question hangs there. You hesitate before you type your reply. You don’t want to be the one to give it a voice. Not until you’re sure. Not until you’re sure sure. And even then, the curious silence in the other corridors you keep an eye on is a confirmation in itself.

And then, the calls begin. Frantic, hushed, a mishmash of disbelief and dread. The nation holds its breath, a collective pause in the rhythm of a Wednesday afternoon.

Finally, the official word. The “breaking news” banners. The “state address” announcement. And everything in between.

We have been here before, with other leaders, other titans.

But this… this feels different.

Because the man with many names was not any other politician. He was a constant. A force of nature. A recurring feature in the long story of our national life. For decades, he has been a central character, the protagonist for some, the antagonist for others, but always, always there.

—

Presence is one thing. Presence can be defined. The definitions may vary, but presence can be defined. But absence? Absence is much more difficult. Because absence isn’t simply nothing - it’s nothing in the place of what once was.

And his absence certainly creates a vacuum, a tear in the fabric of a version of reality Kenya has known for decades.

As the news solidifies, as the digital whispers have become the blaring headlines of mainstream media, one thought, one phrase, settles in my mind, a quiet, insistent refrain:

This will be… complex.

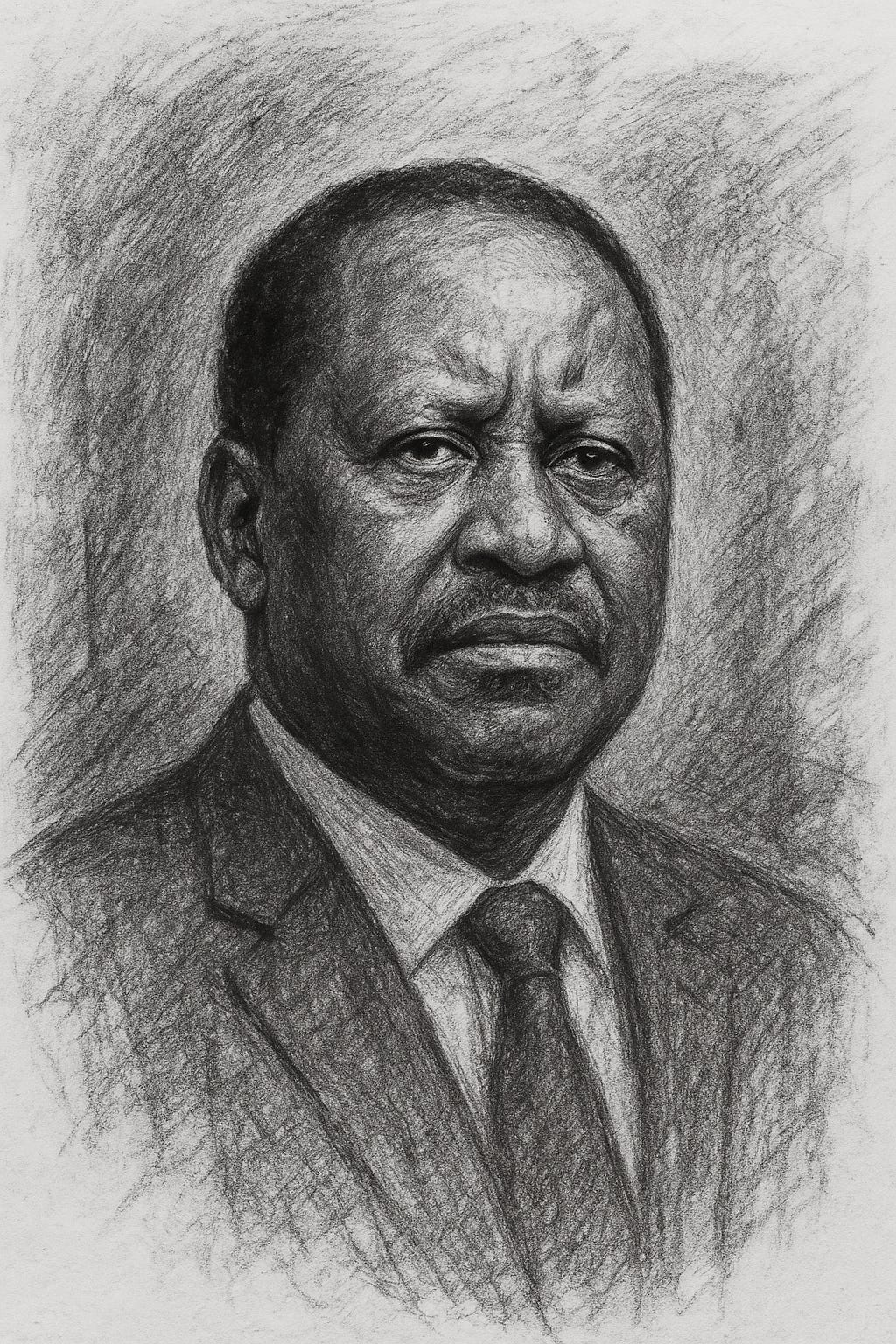

To even begin to understand the man is to accept contradiction as a state of being. There is no simple truth about Raila Amolo Odinga. For how do you eulogise a man who was, in his own way, immortal? How do you summarise a life that was a maelstrom of political passion and personal ambition? I don’t believe you can. I don’t believe it can be done in a single story, nor in a single breath.

—

“Two months after she had died, they came to inform me… It was a very, very painful experience.”

- Raila Odinga, in his autobiography The Flame of Freedom, recalling his detention.

In my mind’s eye, to understand the son, you must first understand the father. Jaramogi Oginga Odinga. The first Vice President of Kenya. A man who cast a long shadow, a shadow that both nurtured and obscured the son who walked within it. Jaramogi was a man of principle, a man who famously fell out with the founding father, Jomo Kenyatta, over ideology and the direction of the new nation. He established a legacy of dissent, a political brand rooted in opposition.

And in that shadow, Raila grew. He was, after all, the scion of one of Kenya’s most formidable political dynasties. This lineage was both Raila’s greatest asset and his most profound cage. It gave him immediate political capital, a fiercely loyal support base in his Nyanza heartland, and a powerful, inherited narrative of righteous opposition to the state. This was the birth of “Odingaism” - that exceptional, almost mystical political hold the family has had over certain segments of Kenyan society. But that same name locked him into the ethnicised dynamics of Kenyan politics. It placed him at the heart of the narrative of a long-standing rivalry between the Odinga (Luo) and Kenyatta (Kikuyu) dynasties. His entire career would become a negotiation: Leveraging his inherited ethnic base as a springboard while desperately trying to build the cross-ethnic coalitions needed to transcend the historical divisions his own name represented.

His education in East Germany, where he received a degree in Mechanical Engineering, had already set him apart from the Western-educated elite - this was at the height of the Cold War, so the place of his education ended up fuelling the state’s suspicion of him as a radical.

But it was the failed coup attempt of 1982 (against then-president Daniel arap Moi) that changed everything, with the state itself serving to complete - and aggrandise - the myth-making. Accused of being a mastermind, he was arrested and charged with treason, a crime punishable by death. Though the charge was later dropped, his punishment was arguably more cruel. He was detained without trial for six years.

Six years. Held in horrific conditions, enduring torture and psychological abuse. The stories from that time are the stuff of legend.

Then, in 1984, his mother died. The authorities, in an act of breathtaking cruelty, waited two months to tell him.

It was a period of devastation that, politically, made him. The Moi regime’s oppression elevated him from activist to political martyr, from mere dissident to a potent symbol of the struggle against tyranny. After his release in 1988, he was detained twice more. In total, he spent nine years of his life in detention. Amnesty International named him a Prisoner of Conscience. This suffering became his armour, the foundational myth of his political life, the primary source of his political legitimacy. It gave him an unimpeachable moral authority in the democratic wave of the 1990s. It is the pure, unadulterated chapter in a life that would become increasingly, and perhaps necessarily, complicated. He was the authentic face of reform, a stark contrast to the politicians who had collaborated with the Moi regime. (We’ll return to this a little later.)

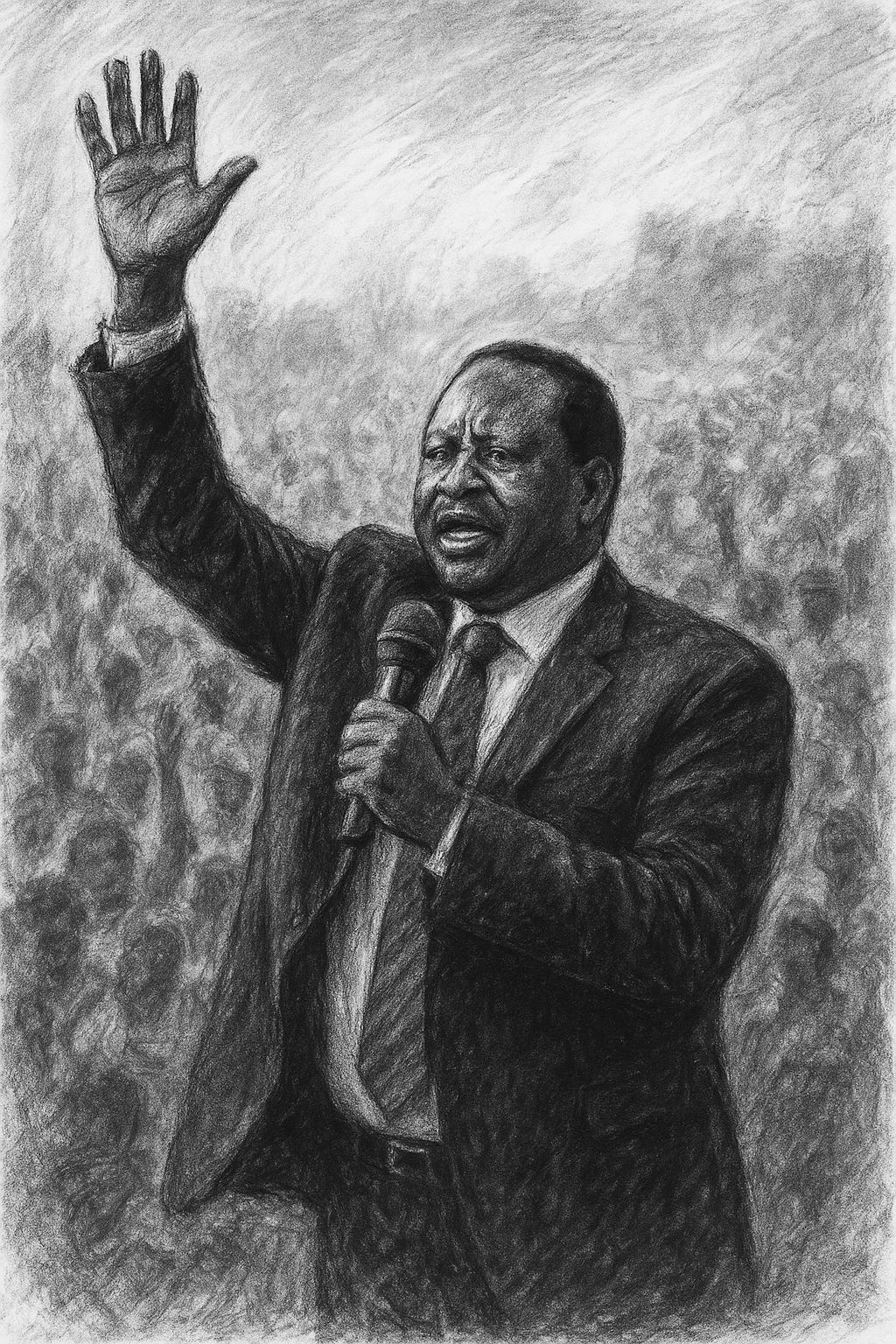

It was during this time that his many names began to emerge, facets of a persona so large that he became a piece of folklore in his own lifetime. For millions, he was simply Baba. Father. A term of endearment that transcended politics and became something deeply personal. Then there was Agwambo. The Mystery. The Unpredictable One. This was the Raila of political strategy, the enigma whose moves you could never quite predict. And, of course, there was Tinga. The Tractor. The force of nature that could clear the way.

Baba. Agwambo. Tinga. The Father, the Mystery, the Force.

—

“Kibaki Tosha!”

- Raila Odinga, October 2002, endorsing Mwai Kibaki for the presidency.

Following his final release in 1991, Raila didn’t just participate in Kenya’s “Second Liberation”; he became one of its central architects. He was on the front line, a “definitive political mobiliser” in the fight to dismantle the one-party state. His election to parliament in 1992 marked his transition from a dissident on the streets to a reformer inside the system.

His greatest institutional achievement is, without question, the 2010 Constitution. The journey there was a masterclass in political strategy. In 2002, his thundering declaration of “Kibaki Tosha!” effectively handed the presidency to Mwai Kibaki, uniting the opposition under the National Rainbow Coalition (NARC). But after being sidelined from a promised Prime Minister post, he found his moment. In 2005, he seized upon an unpopular and flawed government-backed draft constitution and masterfully led the “No” campaign, symbolised by an orange, and brilliantly framed the debate as a populist struggle. The victory offered his career an unparalleled resurgence and gave birth to the Orange Democratic Movement (ODM), his political vehicle and power base for the next two decades.

Then came 2007-08.

I’m going to let that sentence sit for a moment, because I don’t believe we’ve come anywhere close to properly recognising the horrors of that time, let alone reconciling ourselves with the realities they wrought.

—

“The greatness of any nation lies in its fidelity to the constitution... and its strict adherence to the rule of law.”

- Chief Justice David Maraga, delivering the Supreme Court’s nullification of the 2017 presidential election

As Prime Minister in the Grand Coalition Government that followed that 2007-08 crisis (this word feels like such an understatement), he was, by all accounts, instrumental in the delivery and promulgation of the 2010 Constitution. It enshrined a progressive bill of rights and, crucially, established the devolved system of governance he had championed for years - a direct response to the over-centralised presidency that had fuelled so much of our conflict. It stands as his most tangible, enduring legacy.

And here lies one of the profound ironies of his life. Raila, the architect, spent the final decade of his career as the fiercest critic of the very institutions he helped create. He delivered scathing critiques of the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC), the National Police Service (NPS), and the judiciary, accusing them of betraying their constitutional mandates. He argued that despite the new constitution, the same old challenges of electoral malpractice and police brutality persisted. It’s an argument that is, in my opinion, grounded in sufficient observational evidence. This created a deep and complex tension. Was he a principled watchdog, holding institutions accountable to the spirit of the constitution? Or was this the raw frustration of a man who lost three consecutive elections under the new order he had helped build? Was it fair that the independent judiciary he championed, believing it would guarantee fairness, would be the same judiciary to repeatedly act as the official arbiter of his defeats? The answer, like the man himself, is not simple. He was both the celebrated architect and the system’s most deeply frustrated tenant.

—

“I do not know whether Kibaki won the election.”

- Samuel Kivuitu, Chairman of the Electoral Commission of Kenya, December 2007

Raila’s relentless, five-time pursuit of the presidency defined our political landscape for a quarter of a century. It was a recurring national drama of high-stakes campaigns, disputed results, and institutional challenges. The cycle became grimly familiar. He would build a powerful coalition, run a formidable campaign, lose, and then would come the pained contestation of a “stolen victory.” And this grievance wasn’t a hollow one - his narrative was a crucial tool, resonating deeply with his supporters and transforming an electoral loss into an act of profound injustice.

His first bid in 1997 saw him finish a distant third behind Daniel arap Moi. But it was the four consecutive elections that followed that would shape the nation.

The 2007 election was the nadir. The race against incumbent Mwai Kibaki was razor-thin, exercebated by the opaque proceedings that played out. When the Electoral Commission of Kenya (ECK) declared Kibaki the winner at 46% to Raila’s 44% amidst a chaotic tallying process, culminating in that hurried nighttime swearing in ceremony...

One of the things that stayed with a number of people I spoke with was that stunning public admission by ECK chairman Samuel Kivuitu: “I do not know whether Kibaki won the election.” That was fuel to the fire.

Having denounced the judiciary, Raila’s ODM party called for “mass action.”

The dispute ignited a firestorm of political and ethnic violence. Over 1,100 people killed - as far as we were made aware. More than 600,000 displaced - as far as we were made aware. The decision to take the battle to the streets was a key factor in the rapid escalation of the conflict. It is the great stain on his record, a ghost at the banquet of his achievements. The Kofi Annan-led mediation and the creation of the post of Prime Minister stopped the killing - as far as we know. But it also set a murky precedent: That the path to power no longer ran exclusively through the ballot box, but through post-electoral crisis negotiation.

Perhaps resulting from the trauma of 2007, Raila shifted his strategy from the streets to the courtroom, creating another of his paradoxical legacies: The inadvertent institution-builder. In 2013, he challenged Uhuru Kenyatta’s victory at the Supreme Court. The court upheld the result, and Raila, crucially, accepted the verdict and called for peace.

But 2017 was different. He challenged Kenyatta’s victory again. In a historic decision that sent shockwaves across the continent, the Supreme Court, led by Chief Justice David Maraga, did what was therebefore unthinkable: It nullified the presidential election, citing massive illegalities. It was a profound vindication for Raila. It was everything the reformer had ever fought for. And yet, what followed was the paradox. He chose to boycott the court-ordered repeat election, arguing the electoral commission was a crime scene that hadn’t been cleaned. This led to months of brinkmanship, culminating in his “swearing-in” as the “People’s President.”

The cycle ended in 2022 with a final loss, to William Ruto, again upheld by the Supreme Court. He accepted the verdict, albeit grudgingly. Five times he had reached for the ultimate prize; five times it had slipped through his fingers. Inadvertently, his losses had strengthened the very institutions that confirmed them. His quest and persistence had forced the country to confront the demons in its systems, including forcing the Supreme Court to assert its authority - yet his own actions demonstrated the limits of his faith in those very institutions.

It’s… complex.

—

“We have a responsibility as leaders to find solutions. We must bring this country together.”

- Joint Statement by Uhuru Kenyatta and Raila Odinga, March 9, 2018.

If there is one political ritual that defines the latter half of Raila’s career, it is the “handshake.” For him, reconciliation with former enemies became the primary tool for achieving influence, shaping policy, and ensuring stability. But it came at a cost.

This pattern began early. After fiercely opposing President Moi, he stunned everyone by entering into a cooperation agreement with KANU after the 1997 election, eventually becoming a cabinet minister in 2001, in the regime he had fought. Mind you, the same regime that held him without trial and kept him from his own mother’s burial. Mind you, the very 2001 that came right before the 2002 of “Kibaki Tosha!”

The 2008 handshake with President Kibaki was an act of national salvation, creating the Grand Coalition Government and making him Prime Minister.

But it was the 2018 handshake with his then-rival, President Uhuru Kenyatta, that may have been the most transformative, particularly in how it served to either cement perceptions of him, or unmoor (if not outright upend) ideas of him. It ended the decades-long Kenyatta-Odinga rivalry and initiated the Building Bridges Initiative (BBI). For some, it was a statesmanlike act to heal a divided nation. For critics, it was the ultimate betrayal. They argued that he had traded his role as a government watchdog for a share of state power, effectively demobilising the opposition and creating a new grey-zone in which the lines of democratic accountability were significantly blurred.

This pattern repeated a final time after his 2022 loss to William Ruto. A period of anti-government protests over the cost of living in 2024 ended with, almost predictably, Raila on hand with another pact. This “broad-based government” saw his allies appointed to key positions in the Executive and in Parliament, while the state threw in billions in taxpayer funds to support for his bid for the African Union Commission chairmanship. However, it severely damaged his credibility. The youth-led protests of 2024 and the machinations thereafter left the image of Raila - eternal man of the streets - instead now an establishment figure who had made his cynical bargain. These handshakes, seemingly successfully in de-escalating crises, now bore the mark of long-term corrosiveness: The idea that co-optation had become his default post-election strategy; the crippling of the role of the opposition; and the nagging and dangerous sentiment that elections are merely a prelude to power-sharing deals among the elite.

—

“Raila is a chief merchant of impunity... he partook in corruption… a conman”

- Miguna Miguna, in his memoir Peeling Back the Mask

To understand Raila is to confront the contradictions that earned him the name Agwambo. Adn confront them, we must. His brand was built on fighting corruption, yet his tenure as Prime Minister was marred by the 2008 “maize scandal,” where his office was implicated in a scheme involving subsidised grain. Though he was later absolved by parliament in a vote his critics called a political whitewash, the stain remained.

No critic has been more ferocious than his former senior advisor, Miguna Miguna, who levelled several scathing accusations in a tell-all book. Miguna painted a portrait of a leader who was incompetent and lacked true conviction, a “chief merchant of impunity” who “partook in corruption”, a “conman” repeatedly mobilising his supporters for a struggle only to abandon them for personal political gain. His accusations, though deeply personal, give voice to a particular kind of disillusionment - that of the true believer who feels utterly betrayed.

Then there is the paradox of his identity. His Luo identity was the bedrock of his power, providing a fanatically loyal base. Yet this same identity was his Achilles’ heel. His opponents consistently and effectively used his ethnicity to demonise him, creating a powerful counter-mobilisation among rival ethnic blocs. He was both a product of Kenya’s ethnic politics and a catalyst for its intensification.

—

“Odinga never lost an opportunity to reiterate the words of the National Anthem, especially the lines: “Justice be our shield and defender” and, Plenty be found within our borders”.”

- President William Ruto.

And then, perhaps the final, most complex chapter of all. The man who would deliver the official eulogy, who would define Raila’s legacy for the state archives, would be William Ruto. The man who defeated him in his fifth and final presidential race. The man whose entire political persona was built in opposition to the “dynasties” that Raila and Kenyatta represented.

Their journey was a microcosm of Kenyan politics: Allies in the 2007 ODM Pentagon, a formidable political force. Then bitter rivals, facing off in three consecutive, brutal election cycles. Ruto’s “Hustler” narrative was the perfect foil to Raila’s state-backed “Azimio” movement. Each man defined himself against the other.

And yet, in the end, they too had their handshake. The 2024 pact that “ended” the cost-of-living protests brought them full circle, from allies, to enemies, to pragmatic partners in governance. It is the final, ironic testament to Raila’s central role in the Kenyan story: Even in death, his fiercest opponent must acknowledge that the nation is a different one without him.

—

So, who is Raila Amolo Odinga?

Was he the selfless freedom fighter who gave up his best years for the sake of our democracy? Yes.

Was he the charismatic leader who inspired a near-fanatical devotion in millions, giving voice to the voiceless? Yes.

Was he the canny political operator whose handshakes, while alienating some, pulled the country back from the brink on more than one occasion? Yes.

Was he the relentless political combatant whose refusal to accept defeat contributed to our darkest hour? That too, is a part of the story. Yes.

Was he a man of the people, or was he the scion of a political dynasty, forever seeking the power that he felt was his birthright? He was, somehow, both.

The corrosive aspects of his legacy are undeniable. His perfection of “handshake politics” undermined the very essence of opposition, fostering a deep and damaging public cynicism. This is part of the central, maddening contradiction of Raila Odinga. A revolutionary born into privilege. A man of the people who lived a life of immense influence. An outsider who spent his final years as the ultimate insider. He contained multitudes. And we, as a nation, projected our own multitudes onto him. Our hopes, our fears, our resentments, our dreams. He became a screen onto which we projected the complex, fractured nature of our own identity. Our love for him was fierce. Our hatred for him was just as passionate. There was no middle ground with Raila. Indifference was not an option. And, if current conversation is anything to go by, indifference to Raila’s very existence will never be an option.

His passing is the end of an era. A great titan of the Second Liberation is gone. His final legacy will not be a statue. (And I can bet those conversations have already happened in those august WhatsApp groups.) His legacy will be in the very fabric of our noisy, vibrant, and often-frustrating democracy. It will be in the devolution that he championed, in the constitution he was part of fighting for, and in the independence of the judiciary he inadvertently strengthened. It will be in the spirit of resistance that he embodied, the idea that no power is absolute.

And it will be in the complexity. The understanding that our heroes are flawed, that our history is messy, that progress is never a straight line. His existence served as proof that you can be a prisoner and a prince, a fighter and a peacemaker, a hero and, to some, a villain. And perhaps lived one of the ultimate truths: That to be Kenyan is to be all of these things at once.

It would be foolish to breeze over, simplify, or flatten the legacy of a man who has been a central gravitational force in Kenyan politics for well over 30 years. A man who, while never winning the presidency, somehow couldn’t be excluded from governance by the very presidents he ran against. His final legacy, much like his career and the man himself, is destined to remain what the title of this reflection has always suggested it would be: Complex.

What else would you expect of the man with many names?

Knowledgeable, gathered info I didn't know.

Mh! This is it. Comprehensive, elaborate and concise. This is what all should be reading right now.