It started with one elegant word: “Jidishi.”

Of language and the illusion of "intelligence".

It’s three o’clock on a Friday, which in Nairobi is the hour of indecision. The sky can’t make up its mind whether to scorch the earth or drown it - the latter seems to be winning at the moment, quite the plot twist given what the morning looked like. The traffic is holding its breath before the evening’s great exhale of chaos. And I am on my phone, naturally. A quick digital break from the prevailing demands of my other digital screen.

There’s a tweet from Cupcake, a certain “Inaugural Meeting with Eminent Persons Group” - and folks don’t seem to be entirely pleased with the R700 million bill it comes with. Must be nice to be able to publicly critique the government of the day without fear of a squadron of Subarus appearing at your door.

There’s another from Ed Wainaina: “Lactose intolerant people and testing their limits. What’s wrong?” We need to feel alive. Some people skydive, others hike, we choose more accessible rushes - like ice cream. We need to feel alive, Ed. And I shan’t be told how to live.

There’s Ngartia sending out an[other] urgent appeal for blood - for Allan, Patrick, and Solomon. A visceral reminder that there is a real, human cost to corruption, except now the cost is measured in actual blood.

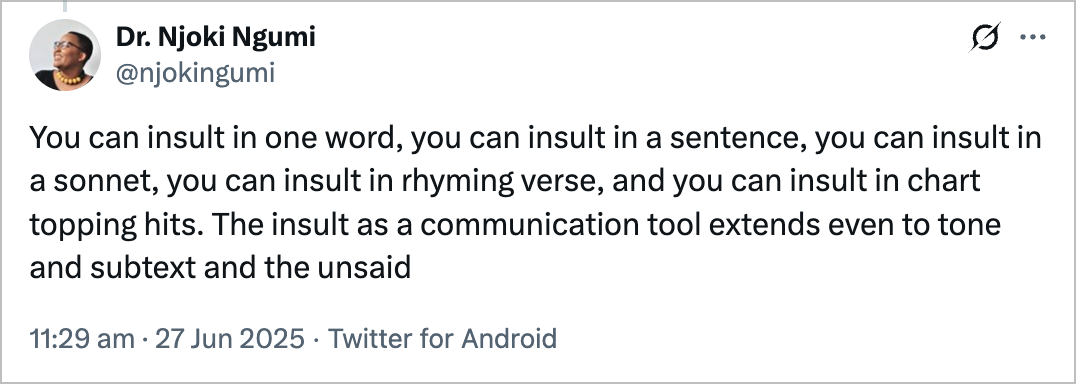

And then, a tweet. One that I had, admittedly, spotted earlier, but caught my attention again this afternoon. Like a small stone tossed into the churning river of the timeline, but its ripples catch the light, written in that effortless Nairobi cocktail of English and Swahili:

I pause for a moment. Then chuckle. Then open my notes app, because for some reason, I hate drafting on Google Docs.

Tupunguze please. A polite, almost gentle request that carries the blunt force of judgement.

It’s not the sentiment that grabs me by the collar. Linguistic purism is a tale as old as tongues. There have always been guardians at the gate of language, convinced that new words are a sign of civilisational decay. Heck, I was one such guardian in my younger days.

No, the thing that hooks deep into the flesh of my curiosity is the reasoning. The why.

“It's not intellectual and doesn't sound intelligent at all.”

There it is. The quiet part, out loud. A verdict passed not on a word’s meaning or utility, but on its very sound, its texture, its pedigree. The word in the dock: ‘Jidishi’. A reflexive verb that has decided to become a whole mood. A dismissal, a challenge, a boast, a joke. In all its defiant, inventive Sheng glory.

And it had been weighed on a set of invisible scales, the kind calibrated in a cold, distant, lost empire, a long time ago. It had been weighed and found wanting.

The question that settled in my mind wasn’t just about a single word anymore. It was bigger, deeper, more uncomfortable.

Who taught us what intelligence is supposed to sound like? And why, after all this time, are we still taking notes so diligently?

In primary school, mockery was currency. A classmate pronouncing a word in a manner different to its English origin was met with snickering or outright laughter: The ‘l’ in “lion” tripping over itself in to an ‘r’, the ‘b’ in “biology” softening into an ‘mb’, the the ‘sh’ in “shilling” slipping into an ‘s’… It’s mockery teachers didn’t put that much effort into discouraging.

Yet that was nothing compared to the true cardinal sin: Being caught speaking Sheng, or your own mother tongue. That was a deeply punishable offence.

This attitude has roots, as Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o’s accounts attest, in the fertile soil of colonial Kenya: “…one of the most humiliating experiences was to be caught speaking Gikuyu in the vicinity of the school. The culprit was given, corporal punishment - three to five strokes of the cane on bare buttocks - or was made to carry a metal plate around the neck with inscriptions such as I AM STUPID or I AM A DONKEY.”

Pure psychological warfare. This is a child being taught, through the eloquent language of shame, that his own tongue - the vessel of his people’s stories, jokes, and philosophies - is worthless. He is learning that intelligence has an accent, and it is not his own.

This isn’t a hypothetical. This was the system. This was the engine room of the colonial project. Ngũgĩ gave this process a chilling name: The “cultural bomb.” Its purpose, he explained, was not merely to control, but to “annihilate a people’s belief in their names, in their languages, in their environment, in their heritage of struggle, in their unity, in their capacities and ultimately in themselves.”

The bomb detonated generations ago, but we are still breathing in the fallout. It’s in the air. It manifests in the subtle, almost unconscious way we admire a politician who speaks English with a polished, transatlantic cadence. It’s in the quiet pride we feel when a child masters their English vowels before they can properly construct a sentence in their mother tongue. And it is in the DNA of a tweet that dismisses a word forged in the heart of Nairobi as “unintelligent.”

The physical classroom is gone, but the colonial headmaster remains alive - perhaps thriving - through those of us dutifully policing our own linguistic spaces, enforcing the old rules, never stopping to ask why.

And in the decades since Kenya’s ‘independence’, the Kenyan establishment has treated Sheng like a troublesome, slightly delinquent sluggard hanging about the town. It’s fascinating, sure, but you wouldn’t want it dating your daughter or representing the family at a formal function.

Which is certainly a profound failure of observation: Sheng is not a corruption. It is a creation. It is not a dialect. It is a living, breathing, evolving testament to the resilience, youthfulness, and sheer intellectual agility of the Kenyan populace. It was born in a space and time when a kid from Nyanza needed to speak to a kid from Central, and neither of their mother tongues would do. So Kiswahili was the base, English was the spice, but the soul of it, the grammar and the swagger, was something entirely new.

It is a language built on a shared chassis with parts playfully picked up from all over the world. It has rules. You can’t just throw words together. There is a syntax, a morphology, a music to it. The way it can take an English word like ‘police’, strip it down, and turn it into ‘mbaru’ as a reference to the brand of car most commonly associated with them? It is efficiency. It is poetry.

And it is not static. The Sheng my mom and dad might have had in the 80s is a different beast from the Genge-infused Sheng of the early 2000s that I grew up with. That Sheng, in turn, is now almost vintage compared to the hyper-fluid, TikTok-driven Sheng of today, where a word like ‘shembeteng’ can be born on a Tuesday and become a national inside joke by Friday. This isn’t decay; it is language moving at the speed of culture. It's a real-time record of our social history.

But let’s add yet another layer here: Sheng is not a perfect, utopian tool of unity. It can also be a fence. The Sheng spoken in Kayole is different from the Sheng of Buruburu, which is different from the Sheng spoken in Kilimani, which certainly different from what the Karen folk call Sheng. It has variants as many as there are streets in the different urban centres across the country. It can be a shibboleth, a way to instantly identify an outsider, to mark territory. It is a tool, and like any tool, it can be used to build bridges or to put up walls.

But to deny its complexity, its power, and its intellectual weight is to refuse to see a people as they truly are.

Now, let’s be fair. Perhaps the sentiment behind the original tweet is not just about snobbery. It may be more complicated than that. It is rooted in a deep, and not entirely unreasonable, fear.

It may be the fear of the parent who has fought their way into the middle class, who has sacrificed everything to give their children the education they never had. They mastered the Queen’s English. They learned to write the perfect cover letter. They know the rules of the game. And they may look at their child, fluent in a language of the street that they can barely understand, and they are terrified.

They may be terrified that this language, this Sheng, will lock their child out of the rooms they worked so hard to get into. They may fear it will be a mark against them on a job application, a signal to the powers-that-be that this child is not ‘serious’, not ‘professional’, not ‘one of us’. The doormen of the corporate world, of academia, of power, are real. And linguistic profiling remains their primary weapon.

This fear is not an illusion. It is a rational response to the very real economic and social hierarchies that govern our lives. It is the heart of the post-colonial dilemma: The gnawing suspicion that to be fully, authentically ourselves is to be professionally and economically disadvantaged. And so we find ourselves pleading with our own children, “Tupunguze, please,” in a desperate attempt to protect them from a system that we resent but still believe in.

It’s a numbing paradox.

This leaves any Kenyan artist, writer, musician, or filmmaker standing at an intriguing intersection.

Part of the syllabus in Kenya was the study of English literature. West African writers such as Chinua Achebe seemed to take an approach that piqued my curiosity: They had a tendency to take the English language, the very tool of their people’s oppression, and bent it to their will. Achebe, for instance, forced English “to bear the burden of my African experience.” He did not write English like an Englishman. He made English speak Igbo, infusing it with the latter’s proverbs, speech patterns, and cultural references, making the former resonate with African life and sensibility. A sensational act of intellectual appropriation.

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, standing at the same crossroads as Achebe, chose a radically different path. Where Achebe believed English could be bent to carry the weight of African experience, Ngũgĩ argued that the master’s tools could never truly dismantle the master’s house. For him, writing in English - no matter how artfully done - was still living in a cell built by colonialism, even if you hung your own art on the walls. So, Ngũgĩ turned his back on English and embraced Gikuyu, insisting that true liberation meant reclaiming the language of his people and restoring its place at the heart of African storytelling.

Today, this is not a theoretical debate. It is the daily dilemma of the creator. Do you write your song with enough English hooks to get it played on international radio? Do you write your novel in a way that is easily translatable for a Western audience? Or do you create something so fiercely, unapologetically local that it resonates in the bones of your own people, even if it remains illegible to the outside world? And that question is, in itself, presumptive: Who even says that it will remain unintelligible in its unapologetic authenticity?

Then in comes Sheng, in its glorious, messy, hybrid nature, offers a third path. (I really wanted to add in an image of that “La Casa de Papel” / “Money Heist” meme. You know the one.) Sheng presents a path for the ultimate code-switcher. It looks at the Achebe path and the Ngũgĩ path and refuses to choose. It is a living embodiment of a generation that sees no contradiction in being simultaneously urban, African, and globally connected. It is, perhaps, the most honest expression of our modern identity.

For the longest (deliberate Kenyanese is deliberate), I used language as outfits: English suit for the office, nice Swahili kanzu for my time in Mombasa, comfortable jeans & t-shirt of Sheng or Dholuo with family & friends, soupçon of French when feeling fancy… A costume cut for its occasion, a performance curated for its stage.

I don’t think that way anymore. It’s exhausting. And it’s a lie.

Words mean things. And language is not a costume. It is a home. It is the architecture of your thought. And a home should not be a series of stage sets. It should be a place where you can be whole. It should have a kitchen where you can make a mess, a living room where you can entertain guests, a private room where you can be quiet, and a big, open veranda where you can laugh out loud.

Which is all my long-winded way of saying: Language is a thing to be comfortable in, regardless of tongue or circumstance. It’s not a thing to be used to measure the worth of an individual based on whether they can speak another’s tongue or not. Language, in whatever form it takes, in whatever way a person or group of people choose to use it, is uniquely theirs, as is their right.

The slow, often painful work of decolonising our minds is, ultimately, the work of building a linguistic home that is big enough for all the parts of ourselves to live in. It is the act of giving ourselves permission to be brilliant, complex, and profound in every language we speak.

So when I hear a word like ‘jidishi’, my first instinct now is to resist the urge to reach for the old colonial yardstick. To resist the echo of the headmaster’s cane. To instead ask a different set of questions. What is this word doing? What reality is it describing? What joy, what pain, what sentiment is it giving voice to?

If we listen closely, what we’ll hear is not the sound of intelligence being diminished. We will hear the sound of it being forged, in real-time, in the vibrant, chaotic, and beautiful richesse of the Kenyan street. We will hear the sound of a people defining themselves, for themselves.

And on this specific matter, if you disagree, I have one word for you.

Jisosi.

ukweli usemwe...i plan to use this sometime soon.very fulfilling remark!!

Eh!🙌🙌