I'm Kenyan. I Don't Write Like ChatGPT. ChatGPT Writes Like Me.

I'm calm. I'm calm. I promise.

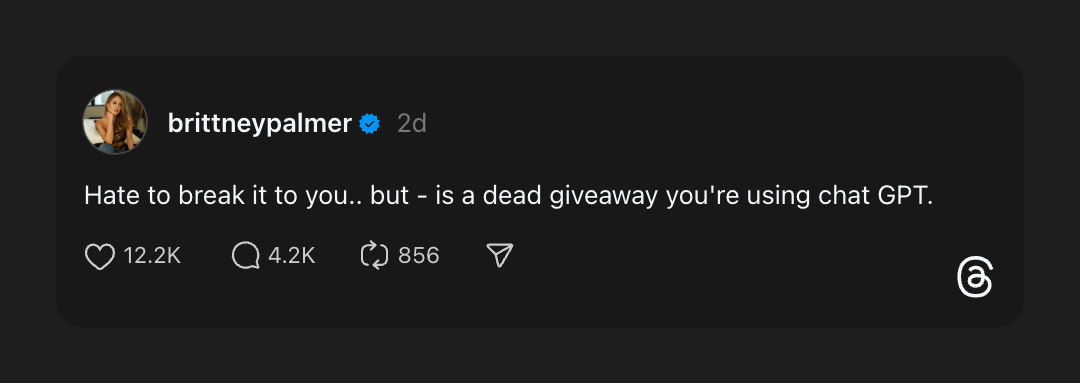

There’s this conversation that keeps happening, and… ok. Ok. This is the post that finally set me off.

The replies pointed out something crucial, something that makes this whole debate even more infuriating: Some of us actually had to learn English.

Let me explain.

The first incident - and perhaps what I should have taken as a sign of times to come - was earlier this year. I received a reply to a proposal I had laboured over for days.

“This is a really solid base, but could you do a rewrite with a more human touch? It sounds a little like it was written by ChatGPT.”

Human touch. Human touch. I’ll give you human touch, you—

Sorry. The intrusive thoughts were having a moment there. I’m back, I’m back.

Here’s the thing: More and more writers seem to be getting these sort of responses, and there is - in my observational opinion - a rather dark and insidious slant to it. Stay with me for a moment, and I’ll get back to that.

Part of the irony is of the flavour that would make our ancestors chuckle. Because the accuser, in their own way, wasn't entirely wrong. My writing does share some DNA with the output of a large language model. We both have a tendency towards structured, balanced sentences. We both have a fondness for transitional phrases to ensure the logical flow is never in doubt. We both deploy the occasional (and now apparently incriminating) hyphen or semi-colon or em-dash to connect related thoughts with a touch more elegance than a simple full stop.

With a calmer mind, I became a little more gracious. The error in their judgment wasn't in the what, but in the why. They had mistaken the origin story.

---

I am a writer. A writer who also happens to be Kenyan. And I have come to this thesis statement: I don't write like ChatGPT. ChatGPT, in its strange, disembodied, globally-sourced way, writes like me. Or, more accurately, it writes like the millions of us who were pushed through a very particular educational and societal pipeline, a pipeline deliberately designed to sandpaper away ambiguity, and forge our thoughts into a very specific, very formal, and very impressive shape.

There’s a growing community (cult?) of self-proclaimed AI detectives, who have designed and detailed what they consider tells, and armed their followers with a checklist of robotic tells. Does a piece of text use words like ‘furthermore’, ‘moreover’, ‘consequently’, ‘otherwise’ or ‘thusly’? Does it build its arguments using perfectly parallel structures, such as the classic “It is not only X, but also Y”? Does it arrange its key points into neat, logical triplets for maximum rhetorical impact?

To these detectives of digital inauthenticity, I say: Friend, welcome to a typical Tuesday in a Kenyan classroom, boardroom, or intra-office Teams chat. The very things you identify as the fingerprints of the machine are, in fact, the fossil records of our education.

---

The bedrock of my writing style was not programmed in Silicon Valley. It was forged in the high-pressure crucible of the Kenya Certificate of Primary Education, or KCPE. For my generation, and the ones that followed, the English Composition paper - and its Kiswahili equivalent, Insha - was not just a test; it was a rite of passage. It was one built up to be a make-or-break moment in life: A forty-minute, high-stakes sprint where your entire future, your admission to a good national high school, and by extension, your life’s trajectory, could pivot on your ability to deploy a rich vocabulary and a sophisticated sentence structure under immense, suffocating pressure.

And that one moment wasn’t an aberration. Every English class and every homework assignment for three years prior (and more, it could be argued) was specifically designed to get the teacher marking your composition to award you a mark as close as possible to the maximum of 40. Scored a 38/40? Beloved, whoever is marking your paper has deemed you worthy of breathing the same air as Malkiat Singh.

It’s a memory that’s hard to write over - the prompt, written in the looping, immaculate cursive of the teacher on the blackboard: “A holiday I will never forget.” Or perhaps it was one of those that demanded that you end the entire composition with, “…and that’s when I woke up and realised it was just a dream.” The topic was almost irrelevant. The real test was the execution.

There were unspoken rules, commandments passed down from teacher to student, year after year. The first commandment? Thou shalt begin with a proverb or a powerful opening statement. “Haste makes waste,” we would write, before launching into a tale about rushing to the market and forgetting the money. The second? Thou shalt demonstrate a wide vocabulary. You didn’t just ‘walk’; you ‘strode purposefully’, ‘trudged wearily’, or ‘ambled nonchalantly’. You didn’t just ‘see’ a thing; you ‘beheld a magnificent spectacle’. Our exercise books were filled with lists of these “wow words,” their synonyms and antonyms drilled into us like multiplication tables.

The third, and perhaps most important commandment, was that of structure. An essay had to be a perfect edifice. The introduction was the foundation, the body was the walls, and the conclusion was the roof, neatly summarising the moral of the story and, if you were clever, circling back to the introductory proverb to create a satisfying, if predictable, loop. We were taught to build our paragraphs around a strong topic sentence. We were taught the sin of the sentence fragment and the virtue of the compound-complex sentence. Our teachers, armed with red pens that bled judgment all over our pages, were our original algorithms, training us on a specific model of "good" writing. Our model compositions, the perfect essays from past students read aloud to the class, were our training data.

And that’s a culture that is carried over into high school, where set books must be memorised, and arguments for or against certain statements must be elaborately made for you do reach and surpass the English literature passmark. You could literally recite Shakespeare in the middle of the night right before any exam.

---

This style has a history, of course, a history far older than the microchip: It is a direct linguistic descendant of the British Empire. The English we were taught was not the fluid, evolving language of modern-day London or California, filled with slang and convenient abbreviations. It was the Queen's English, the language of the colonial administrator, the missionary, the headmaster. It was the language of the Bible, of Shakespeare, of the law. It was a tool of power, and we were taught to wield it with precision. Mastering its formal cadences, its slightly archaic vocabulary, its rigid grammatical structures, was not just about passing an exam. It was a signal. It was proof that you were educated, that you were civilised, that you were ready to take your place in the order of things.

(I’ve tried to resist it, but I can’t help myself, and perhaps you’ve already picked up on it: See the threes?)

In post-independence Kenya, this language didn't disappear. It simply changed its function. It became the official language, the language of opportunity, the new marker of class and sophistication. The Charles Njonjos and Tom Mboyas of their time used it to stamp their status in society. The ability to speak and write this formal, "correct" English separated the haves from the have-nots. It was the key that unlocked the doors to university, to a corporate job, to a life beyond the village. The educational system, therefore, doubled down on teaching it, preserving it in an almost perfect state, like a museum piece.

And right there is the punchline to this long, historical joke. An “AI”, a large language model, is trained on a vast corpus of text that is overwhelmingly formal. It learns from books published over the last two centuries. It learns from academic papers, from encyclopaedias, from legal documents, from the entire archive of structured human knowledge. It learns to associate intelligence and authority with grammatical precision and logical structure.

The machine, in its quest to sound authoritative, ended up sounding like a KCPE graduate who scored an 'A' in English Composition. It accidentally replicated the linguistic ghost of the British Empire.

---

Now, the world, through its new and profoundly flawed technological lens, looks at the result of our very human, very analogue training and calls it artificial. The insult is sharpened by the very tools used to enforce it. The so-called AI detectors are not neutral arbiters of truth. They are, themselves, products of a specific cultural and technical worldview.

These detectors, as I understand them, often work by measuring two key things: ‘Perplexity’ and ‘burstiness’. Perplexity gauges how predictable a text is. If I start a sentence, "The cat sat on the...", your brain, and the AI, will predict the word "floor." A text filled with such predictable phrases has low perplexity and is deemed "robotic." Burstiness measures the variation in sentence length and structure. Natural human speech and writing are perceived to be ‘bursty’ - a short, punchy sentence, followed by a long, meandering one, then another short one. LLMs, at least in their earlier forms, tended to write with a more uniform sentence length, a monotonous rhythm that lacked this human burstiness.

Now, consider our ‘training’ again. We were taught to be clear, logical, and, in a way, predictable. Our sentence structures were meant to be consistent and balanced. We were explicitly taught to avoid the very "burstiness" that ‘detectors’ now seek as a sign of humanity. A good composition flowed smoothly, each sentence building on the last with impeccable logic. We were, in effect, trained to produce text with low perplexity and low burstiness. We were trained to write in precisely the way that these tools are designed to flag as non-human. The bias is not a bug. It is the entire system.

Recent academic studies have confirmed this, finding that these tools are not only unreliable but are significantly more likely to flag text written by non-native English speakers as AI-generated. (And, again, we’re going to get back to this.) The irony is maddening: You spend a lifetime mastering a language, adhering to its formal rules with greater diligence than most native speakers, and for this, a machine built an ocean away calls you a fake.

---

So, when you read my work - when you see our work - what are you really seeing? Are you seeing a robot's soulless prose? Or are you seeing the image of our Standard Eight English teacher, Mrs. Amollo, her voice echoing in our minds - a voice that spoke with the clipped, precise accent of a bygone era - reminding us to connect our paragraphs with a suitable linking phrase? Are you seeing an algorithm's output, or the muscle memory of a thousand handwritten essays, drilled into us until the structure was as natural as breathing?

The question of what makes writing "human" has become dangerously narrow, policed by algorithms that carry the implicit biases of their creators. If humanity is now defined by the presence of casual errors, American-centric colloquialisms, and a certain informal, conversational rhythm, then where does that leave the rest of us? Where does that leave the writer from Lagos, from Mumbai, from Kingston, from right here in Nairobi, who was taught that precision was the highest form of respect for both the language and the reader?

It is a new frontier of the same old struggle: The struggle to be seen, to be understood, to be granted the same presumption of humanity that is afforded so easily to others. My writing is not a product of a machine. It is a product of my history. It is the echo of a colonial legacy, the result of a rigorous education, and a testament to the effort required to master the official language of my own country.

Before you point your finger and cry "AI!", I ask you to pause. Consider the possibility that what you're seeing isn't a lack of humanity, but a form of humanity you haven't been trained to recognise. You might be looking at the result of a different education, a different history, a different standard.

You might just be looking at a Kenyan, writing. And we’ve been doing it this way for a very long time.

When I was in primary school, I used read the dictionary as a hobby. The Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary. Yes, the big one.

A word gave me a synonym, which gave me an antonym. In the midst of all those chaos, I could bumb into an idiom, it's origin, and sometimes I could flip to the back for the word lists.

I could also a whole essay on so let me take a chill pill 😂

Anyway, it's sad how AI no longer gives me the confidence to write.

My thoughts on this are that Kenyan, Nigerian, Ugandan, Zimbabwean, Zambian English (do you see the colonizing trend ) has always sounded robotic.

When I went back into the Kenyan system, having spent my elementary and middle school in an American school abroad, I tried my hardest never to sound like that: in writing and speaking, especially. Which meant that I doubled down on my Western accent and pissed people off because I was attempting to be different, better than them, yet there I was with them, at the same level. More to be unpacked here. I like your article because it highlights the stark difference between the types of English found across societies, which are often misdiagnosed.

AI will adopt a more slang and laid-back way of talking, or rather, a more “human touch”. It makes total sense that the first iteration of AI was basic formal writing; that’s instructional as opposed to creative, because that’s the most significant need globally. Or rather, the biggest point of familiarity and use. From scholarly needs to work requirements, and even general use, it’s the most widely taught and used form of English. Through further interaction and training, it will gradually adopt the slang aspects of the English language. But at this point, it’ll also take up our languages as we create our own.

And yes, it’s not lost on me that I am making your argument for you. English isn’t our first language, and it’s evident because it’s taught to us by those who adopted it too. Our English teachers passed on what they took as ESL students in a harsh system of learn or be discarded. We’re not natives of the language in the sense (although I consider myself to be), or rather, we are with additions of Swahili, Kikuyu, Chichewa, Bemba, Igbo, and that affects how we use English, and not just in accents.

I remember a conversation with a colleague (Western descent) where he pointed out that I had said “I’ll finish that today morning”, as opposed to “this morning”. To his point, it’s more “human” to say “this morning.” To my point, in Swahili, we say “leo asubuhi”, — “today + morning”. A language I juggle that affects, knowingly or unknowingly, how I express myself in English.”

I empathize with you, but can you imagine what a game changer it will be when AIs settle into multi-lingualism? You pay the price of being among the first. We all do.